the interview.

This thesis exhibition opened with the video you see below of my grandmother. We call her Nonni. She has been playing her Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) for over 30 years.

When I visited her in the summer of 2024, I was dismayed to see that her system had stopped functioning. Fortunately, I was able to find her a replacement console, but the ordeal planted questions in my mind.

What happens to the media we own when hardware fails and all that is left is software? Do we really own anything anymore?

the timeline.

This timeline covering the left wall of the exhibition chronicles the bizarre legal coincidences that led to the multibillion dollar proprietary software industry and the absurd century-long copyright term that defines how each of us engage with creative media. The axis of the timeline shows three datapoints: My lifetime, my grandmother's lifetime, and the copyright term of the game I grew up playing with her. That game was Super Mario World which will not enter the public domain until the year 2086.

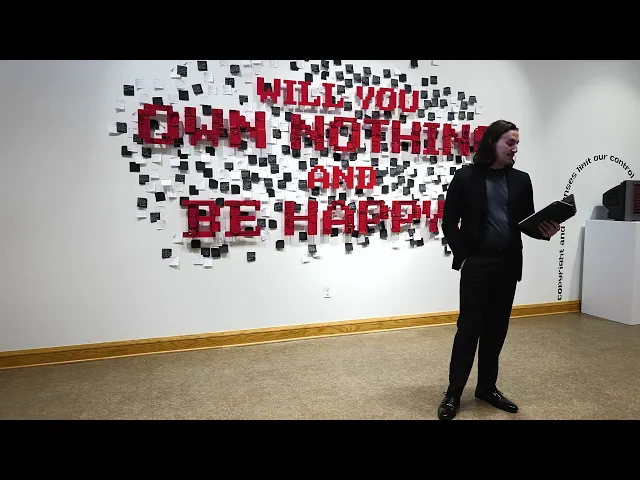

the wall.

The length of the copyright term doesn't just affect how we preserve and reproduce the media we own, it serves as a mechanism for controlling how we use, experience, and share it with the people we love.

If you have ever agreed to a terms-of-service for a software, you have agreed to an end user license agreement (eula). These licenses almost always disallow copying, backing up, and altering the software in any way. They also frequently include forced arbitration clauses. What this means in practice is that it is incredibly difficult to bring a class action lawsuit against the publishing company when consumers like you and I are wronged.

These license agreements prohibit you from having the freedom to fully take advantage of what you pay for, but they can be changed at any time and for any reason by the software publisher.

This dynamic has led to rampant anti-consumer practices across every industry imaginable.

Unjust lawsuits on behalf of media companies, artificial scarcity, planned obsolescence, aggressive threats of legal action, and termination of service are but a few of the examples of this anti-consumer behavior.

The wall is full of such stories from both across the history of contemporary copyright and contributed by visitors to the exhibition.

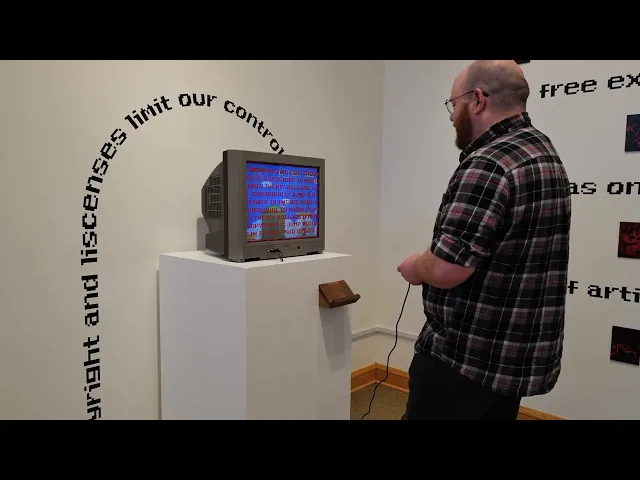

the paywall.

In today's online economy, nearly everyone has had the experience of enjoying a platform or service only for the price to creep up, and for the quality to creep down. Author and Blogger Cory Doctorow coined the term enshittification to describe this platform decay.

This piece "the paywall" imagines if Super Mario World was released today and subject to many of the same enshittification practices. The screen is visibly obscured by legal jargon and prompts to upgrade to a "premium" plan in order to access the full game.

The standard jump button (A) has been disabled leaving only the clumsy "spin jump." The game remains technically playable and beatable, but is transformed from an exciting and artistic experience into a deeply frustrating one.

the copywall.

Despite living our entire lives under this copyright regime, we may imagine a different future by remembering that things weren't always this way. For centuries, going back as far as Aristotle who believed that imitation was a necessary and inevitable part of creative evolution, both on the level of the individual and of culture.

The American founding fathers initially set the maximum copyright term at only twenty-eight years because they believed that a thriving public domain was necessary for the health of public discourse.

In the renaissance and baroque periods, imitation was a required step of apprenticeship and often was driven by market incentive. Patrons of skilled artists often requested specific scenes and conventions that might today otherwise be copyrighted. This wall depicts sixteen iterations of "The Entombment" by sixteen different artists.

the camera obscura.

Many of these baroque artists, famously Caravaggio, were speculated to have used camera obscura to copy live subjects or even copy the compositional outlines of other artists paintings.

The third wall of the exhibition is my own version of a contemporary camera obscura. In 1992, Nintendo released a basic raster painting software for the SNES alongside a mouse peripheral. Mario Paint was many peoples' of my age first experience with digital image-making. However it was entirely ephemeral. There were no output peripherals or ways to keep what one make in the program aside from three save states that could not be transfered from the cartridge.

This Mario Paint camera obscura imagines a solution to that problem by projecting the image of the screen onto a canvas, but it also frames the process of imitation and "copying" as a communal creative experience. Participants absolutely engaged in the infringement of copyrighted material, but they also undeniably collaborated in creating something new.

the game room.

In the center of the room is the answer to the questions raised by the rest of the exhibition: a game room with an emulation machine loaded with thousands of pirated games sourced from dedicated internet archivists.

All of these games are still covered under copyright, and many of them are not legally purchasable or playable on contemporary technology. This means that many of them are only playable by breaking the law. Even if every single game on this machine was legally purchased (and many have been throughout my life), backing them up and playing them on this machine would technically be considered an infringement of copyright.

Media companies have learned that they can use the power of nostalgia the interests we share with our family and friends to hook all of us up to their revenue streams like a group of bottomless IV bags full of money. Art and media we have payed for often multiple times is now only accessible through a steady siphoning of subscription fees. Under these conditions, when buying isn't owning, is piracy stealing?

the exhibition.

the research.

This subject of this research was developed primarily from the book Who Owns this Sentence by David Bellos. Design inspiration and theory was taken from many sources including the typographic compositions of Stefan Sagmeister, the theory of Discursive (critical) design as defined in Discursive Design by Bruce M. and Stephanie M. Tharp, the methodology for information design of Edward E. Tufte in his book Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative, Countless activists and protest artists featured in the Letterform Archive's exhibition Strikethrough, and many others.

This exhibition and research was also built upon a mountain of support from family, friends, mentors, and even complete strangers. Each of our lives and creative output are the result of thousands of tiny contributions to us. This is why art and media shouldn't be hoarded like gold under a dragon, and it is also why at the end of the exhibition, each piece and any images of the exhibition were dedicated to the public domain through a Creative Commons CC0 license.